Monastery of Sant Pere de Rodes

Sant Pere de Roda / Sancti Petri Rotensis

(el Port de la Selva, Alt Empordà)

The origin of the monastery is shrouded in ancient tales. Despite the advances in our knowledge of the early days of this house, archaeological and historical questions give the place a certain legendary feeling. Those stories also speak of the body, or relics, of Saint Peter and other saints, deposited in this place since ancient times. Jeroni Pujades places the arrival of those relics at the beginning of the 7th century, in the time of Pope Boniface IV.

What is certain is that next to the monastery are some structures of very ancient origin, possibly Roman, and that small, decorated marble fragments from that period, later reused, come from this place. The first historical records date back to 878, in a precept of King Louis II the Stammerer, where the place is mentioned as a monastic cell dependent on Sant Esteve de Banyoles. At this time, Sant Pere was part of a group of four cells (together with Sant Joan Ses Closes, Sant Cebrià de Penida y Sant Fruitós de la Vall de Santa Creu) that were the subject of a dispute between Banyoles and Saint-Polycarpe de Razès, in Languedoc.

At this time there must have been very simple buildings, of which some traces have been found. The last prior of this centre was Tasi, who we find mentioned in 944 with this title. At that time Santa Maria de Roses depended on him. Around 947, Rodes was consolidated and gained independence from Banyoles, achieving a hegemonic position in the territory. Its first abbot was Hildesind (947-991), son of Tasi. The life of a great monastery began, the church was built, which was consecrated in 1022, and which, partially modified later, is the one we can still see today.

From 1100 onwards, and throughout the 12th century, the monastery underwent renovation work, perhaps due to the destructive effects of the disputes between the houses of Peralada and Empúries, which affected the monastery. It was then that the narthex was built, a new doorway, and later the third, that of the Master of Cabestany, to be dated between 1160 and 1163. This work was destroyed when the monastery was abandoned and now only a few fragments remain, the most important being the one in the Museu Marès in Barcelona, with the Apparition of Christ to the Apostles, and a beautiful capital in the Museum of Peralada. The new cloister was also built. The monastery enjoyed great vitality until the end of the 14th century, but then fell into decline, with the relaxation of community life, lack of donations to the monastery... to which must be added the effects of the Black Death (1345), which claimed the lives of twenty-four monks.

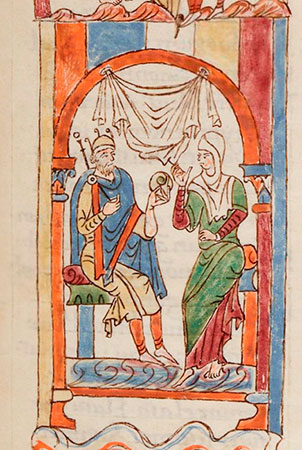

Fear of piracy led to the place being fortified. From 1447 onwards, the centre was run by commendatory abbots who aggravated its decline. In 1654, the site was abandoned for six years because of the war, which marked the beginning of the plundering of its assets. The effects of the war with the French led to successive looting. The Rodes Bible, now in the National Library of France, was plundered in 1693. In the 18th century it reached a state of total decay. In 1726 it was sacked again and in 1798 the community moved to Vila-sacra and then to Figueres (1809). After years of abandonment and sacking, the imposing and highly complex remains of the monastery began to be protected and, especially from the last decade of the 20th century onwards, studied and restored.

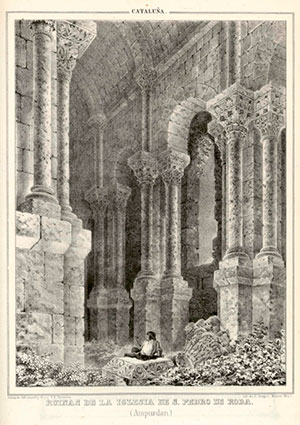

The oldest surviving remains can be dated back to Roman times, while the earliest monastic remains may date back to the 8th century. The church that still survives is basically the one whose construction began around the year 1000. There has always been controversy about this church because it departs from the usual construction systems of the time. It is a building with three naves (the side naves are very narrow), a transept and three apses, the central one with an ambulatory and a parabolic floor plan, the side apses are in the transept. The central nave is covered with a barrel vault supported by pillars with attached columns, on a very high base.

The main doorway, formerly decorated in marble by the Master of Cabestany, leads to a narthex. This narthex was built after the construction of the church. The original façade was in the open air and had a doorway, apparently decorated, and three windows, one for each nave. The first cloister, recently discovered, was also built at that time, under a later one. It was quadrangular in plan and was based on a solid construction with large arches and barrel vaults. From here it was possible to access the various rooms that disappeared with the construction of the new cloister.

The work continued with the construction of the second cloister, which has been restored, although the capitals are scattered in various places. Mention should also be made of the bell tower, possibly built between the 11th and 12th centuries. It is matched by a defence tower, or keep, which is also ancient, dating from the 10th century, with later modifications. The monastery's monumental ensemble, although it has suffered all kinds of despoilment and is in ruins, still impresses thanks to the restorations and the singular beauty of its church.

- ADELL, J. A. i altres (1997). Sant Pere de Rodes (Catalunya). La cel·la i el primer monestir. Annals de l'Institut d'Estudis Gironins. Vol. 38

- ALCOY I PEDRÓS, Rosa (1987). Bíblia de Rodes. Catalunya romànica. Vol. X. El Ripollès. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana

- BADIA I HOMS, Joan (1981). L’arquitectura medieval de l’Empordà. Vol. II-B. Girona: Diputació de Girona

- BADIA I HOMS, Joan; CASES I LOSCOS, M. Lluïsa (1990). Catalunya romànica. Vol. IX. L’Empordà II. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana

- BARRACHINA, Jaime (1999). La portada de Sant Pere de Rodes. Locus Amoenvs, 4

- BOLÓS, Jordi; HURTADO, Víctor (1999). Atles del comtat d’Empúries i de Peralada (780-991). Barcelona: Rafael Dalmau Ed.

- BUSCATÓ, Lluis (2005). Propietat privada versus patrimoni històric i arqueològic. L’exemple del monestir de Sant Pere de Rodes. Annals de l'Institut d'Estudis Gironins. Vol. 38

- COSTA BADIA, Xavier (2019). Paisatges monàstics. El monacat alt-medieval als comtats catalans (segles IX-X). Tesi doctoral. Universitat de Barcelona

- GAVÍN, Josep M. (1983). Inventari d’esglésies. Vol. 13, Alt Empordà. Barcelona: Arxiu Gavín

- GUITERT I FONTSERÉ, Joaquim (1927). Monestir de Sant Pere de Rodes. Barcelona: Casa P. Caritat

- LORÉS, Immaculada (2002). El monestir de Sant Pere de Rodes. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona i altres. Barcelona

- MAROT, Teresa (1999). El Tresor de Sant Pere de Rodes. Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya. Barcelona

- PAPELL, Antoni (1930). Sant Pere de Roda. Figueres: Ideal

- PIFERRER, P. (1843). Recuerdos y bellezas de España. Cataluña. Vol. 2

- PLADEVALL, Antoni i altres (1986). Diversos articles a: Lambard: Estudis d’art medieval. Barcelona: I. E. Catalans

- PLADEVALL, Antoni i altres (1989). Sant Pere de Rodes, un monestir enigmàtic. Espais, núm. 18

- PLUJÀ, Arnald; MASMARTÍ, Sònia (2013). Els dominis de Sant Pere de Rodes al Cap de Creus. Aj. del Port de la Selva

- PUIG, Anna Maria; MATARÓ, Montserrat (2012). La cel·la abans del monestir. Sant Pere de Rodes als segles VIII i IX. Annals de l’Institut d’Estudis Empordanesos. Vol. 43

- PUJADES, Geroni (1609). Coronica universal del principat de Cathalunya. Barcelona: Margarit

- PUJOL I CANELLES, Miquel (2010). El trasllat de la comunitat del monestir de Sant Pere de Rodes al castell de Vila-sacra. Miscel·lània en honor de Josep Maria Marquès. Diputació de Girona, Publicacions de l´Abadia de Montserrat

- RIU-BARRERA, Eduard (2000). Implantació territorial i forma arquitectònica dels monestirs de la Catalunya Comtal (s. IX-XI). 1r. Congrés d'Arqueologia Medieval i Moderna de Catalunya

- SUBIAS GALTER, Joan (1948). El monestir de Sant Pere de Roda. Barcelona: Ariel

- VILLANUEVA, Jaime (1851). Viage literario a las iglesias de España. Tomo. XV. Real Academia de la Historia. Madrid