Monastery of San Millán de Suso

Monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla / S Emiliani

(San Millán de la Cogolla, La Rioja)

The ancient monastery of San Millán has its origins in the place of Suso, in the cave where the anchorite Saint Aemilian (Millán or Emiliano) retired, where he died in 574. This figure is known thanks to his biography, written shortly after his death by the bishop of Saragossa, Saint Braulio, which makes this account very plausible. A group of his followers gathered around the figure of Saint Aemilian in what was to be the origin of the monastery.

The monastery that had been established had a dual character, housing both monks and nuns, and continued after the saint's death. Although there is no documentation to prove it, it seems that it continued to be active during the years when this territory was occupied by the Muslims in a way that seems to have been not very aggressive. Once the territory was recovered (Nájera was occupied in 923), documents mentioning the monastery began to be found. The first known document dates from 942 and refers to the entry of a monk into the community; in 947, Abbot Esteban is mentioned. As for the buildings, a Mozarabic church with a single nave was consecrated in 959, using one of the caves as a presbytery. Some manuscripts from this period, produced in the monastery, have been preserved. These documents, together with others brought from other places, formed an important library, above what was usual at the time, and which would become richer with the passing of time.

The life of Saint Aemilian (473-574) was chronicled by Braulio, Bishop of Zaragoza between 631 and 651, lending significant credibility to the narrative. Aemilian was a shepherd, a native of Berceo, who at the age of twenty came into contact with the hermit Felix (Felices), becoming his disciple. After returning to his homeland, he lived briefly in Suso before withdrawing as a hermit, apart from the world, where he remained for forty years. Following a short period during which he tended to the spiritual needs of the parish of Berceo, he returned to Suso, where he remained until his death. Both during his life and after his passing, Aemilian was associated with numerous miraculous events.

The church of Suso was modified over time: the enlargement of the church and the change of orientation (east-west), resulting in a two-nave church with an apse integrated by the previous church (with a north-south orientation), as well as the addition of a gallery on the south side, are still of Mozarabic construction. At the beginning of the 11th century, the church was extended with an addition to the nave and its orientation was slightly modified. After the death of Saint Millán, his body was buried in the same place where he had lived, and it was not until 1030 that his remains were placed in a silver urn kept in the same church. Shortly afterwards, in 1053, the relics were removed with the intention of taking them to Santa María la Real de Nájera, but, miraculously, they did not go beyond the site of Yuso (the present-day monastery of San Millán de Yuso), where they remained. In fact, it seems to have been a transfer from Suso to Yuso, where in 1053 the monastery was already built, at least for the most part.

In Yuso, the remains were kept in a magnificent casket made of ivory, gold and precious stones. At the end of the 12th century, a chapel was built in Suso, in one of the caves, where a cenotaph with the figure of the saint was placed. Since the transfer of the relics to Yuso and with the new monastery in the valley, the activity of the first establishment must have been very limited, probably maintaining the double character and following a Visigoth rule, while in Yuso the rule of Saint Benedict was already being observed. Later there is little documentation that refers to it, around 1100 it must have disappeared as a monastery and it is known that it was occupied by some monks from Yuso who lived there, and small interventions were also made that changed its appearance.

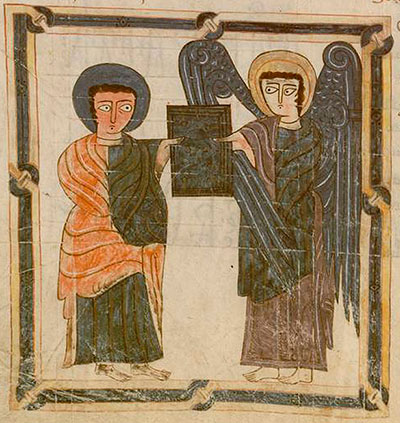

The Real Academia de la Historia in Madrid preserves a significant number of medieval codices originating from the monasteries of San Millán de la Cogolla, some of them produced locally. Among these documents are three notable Beatus manuscripts: one held by the aforementioned Real Academia, another in the library of the Monastery of El Escorial, and the third in the National Library of Spain. Also of great importance are the Glosas Emilianenses, a document created between the 10th and 11th centuries, containing clarifying annotations added to the main Latin text. Despite ongoing debates, these marginal notes are widely considered to be among the earliest known examples of the Spanish and Basque languages.

- ANDRÍO, Josefina; i altres (1996). La necrópolis medieval del monasterio de San Millán de la Cogolla de Suso (La Rioja). Berceo

- BALLESTEROS, Manuel. (1944). Los marfiles de San Millán de la Cogolla de Suso. Saitabi, núm. 2

- CABALLERO, Luis (2002). La iglesia de San Millán de la Cogolla de Suso: Lectura de paramentos 2002. Arte medieval en La Rioja. Instituto de Estudios Riojanos

- CADIÑANOS, Inocencio. (2000). El Monasterio de San Millán según un dibujo de comienzos del siglo XVII. VI Jornadas de arte y patrimonio regional. Gobierno de La Rioja

- CAPELLÁN, Gonzalo (2001). El monasterio de San Millán y la desamortización. Berceo, núm. 140

- DE LAS HERAS, María de los Ángeles (1986). Las tablas de San Millán de la Cogolla. Segundo Coloquio sobre Historia de La Rioja

- GARCÍA TURZA, Javier (2013). El monasterio de San Millán de la Cogolla, una historia de santos, copistas, canteros y monjes. Lleó: Everest

- GIL-DIEZ USANDIZAGA, Ignacio (1997). Los monasterios de San Millán de la Cogolla. Historia y patrimonio artístico. Berceo, núm. 133. Instituto de Estudios Riojamos

- GÓMEZ, I. M. (1963). Émilien. Dictionnaire d'histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques. Vol. 15. París: Letouzey et Ané

- IBÁÑEZ RODRÍGUEZ, Miguel (1997). La constitución del primer cenobio en San Millán. Instituto de Estudios Riojanos

- LEDESMA, María Luisa (1989). Cartulario de San Millán de la Cogolla (1076-1200). Zaragoza: Textos medievales, 80

- LEJÁRRAGA, Teodoro (2012). El monasterio de San Millán de Suso. Patrimonio de la Humanidad. Logronyo: Ed. Emilianenses

- MAESTRO, Ismael (1996). Reflexiones en torno a las iglesias y monasterios de San Millán de la Cogolla (siglos X-XI). Príncipe de Viana, vol. 57

- MARTÍNEZ DÍEZ, Gonzalo (1997). El monasterio de San Millán y sus monasterios filiales: documentación Emilianense y diplomas apócrifos. Brocar, núm. 21

- MOYA OLLER, Anna (2017). Ascetisme i monacat tardoantic a la tarraconense (ss. IV-VII). Una aproximació sociocultural i arqueològica. Tesi Doctoral. Tarragona: Universitat Rovira i Virgili

- OLARTE, Juan B. (1995). Monasterio de San Millán de la Cogolla. Suso y Yuso. Lleó: Edilesa

- PALACIOS, Juan Manuel (1959). En torno al arca de San Millán de la Cogolla. Berceo, núm. 51

- PEÑA, Joaquín (1994). San Millán de la Cogolla, páginas de su historia. San Millán de la Cogolla: Monasterio de Yuso

- PUERTAS, Rafael (2000). San Millán de Suso y la iglesia mozárabe de Bobastro. VI Jornadas de arte y patrimonio regional. Gobierno de La Rioja

- SANDOVAL, Prudencio de (1601). Primera parte de las fundaciones de los monesterios del glorioso Padre San Benito. Madrid: L. Sánchez

- UBIETO, Antonio (1976). Cartulario de San Millán de la Cogolla (759-1076). València: Textos Medievales, 48