It was Ramon Berenguer IV (Count of Barcelona between 1131 and 1162) who took the decision to build a monastery in the lands that had just been conquered from the Saracens, with a dual purpose: on the one hand, the repopulation of the area and, on the other, a religious one. The Cistercians, who at that time had a strong presence in Provence, were chosen to cover this second aspect.

In 1150 or 1151, he approached Abbot Sanche de Fontfroide (Aude) and gave him the land to build this new establishment. In 1151 the abbey of Fontfroide (Aude) sent the first monks to prepare the new settlement, which was to be operational by 1152, although it was not formally established until 1153. Alfonso II, son of the founder, confirmed Poblet's possessions, as well as making him the beneficiary of other donations and granting him protection. In 1186, this king gave the land necessary for the foundation of a new settlement in Piedra (Aragon), as well as choosing Poblet as a burial place.

At the end of the 12th century and throughout the 13th century, the monastery suffered a period of economic crisis, however, other foundations were made from Poblet: Santa Maria de Piedra, in 1194, where they had a castle. Santa Maria de Benifassà, also a castle of Muslim origin that passed into the hands of Pere de Cervera, later a monk of Poblet who obtained ownership of the place and in 1233 materialised the foundation. Santa Maria La Real de Mallorca, in operation in 1240. Also, the priories of Sant Vicenç de la Roqueta (Valencia), owned by Poblet from 1288 and that of Natzaret in Barcelona, founded between 1311 and 1312. In addition to these foundations, Poblet had a long series of farms (seventeen), characteristic of Cistercian houses and which allowed for the agricultural exploitation of their possessions. The first monks who came to Poblet probably settled provisionally on the Mitjana farm (to the west of the monastery) while they proceeded to erect the first buildings on the site of the definitive settlement.

The first constructions of the definitive monastery were those still standing on the eastern side, next to the wall: the Joc de Pilota hall (c. 1163), perhaps at that time a church and dormitory, as well as the chapel of Sant Esteve (1180). The large monastic church was built between 1166 and 1185. It is a building with three naves with a transept and a complex chevet compared to other Cistercian constructions of the period. Around the presbytery there is an ambulatory with five radial chapels, which complement the two open apses in the arms of the transept. A galilee was built in front of the building, which was later masked by the wall and the added Baroque façade.

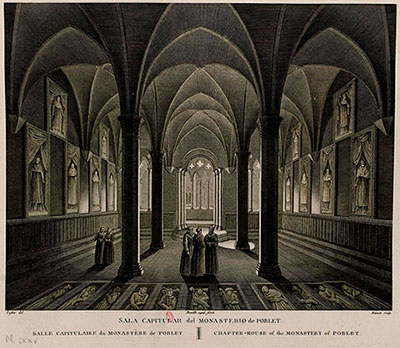

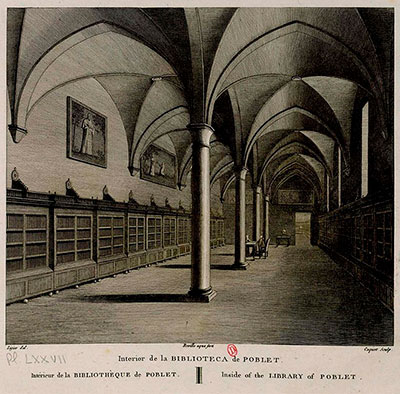

Between the 12th and 13th centuries work began on the main cloister, on the south wing and the cloister fountain, the oldest parts. The heating room and the cloister of Sant Esteve were also built in this sector. The magnificent refectory also dates from this period. In the first half of the 13th century, major works were carried out outside the enclosure and the chapel of Santa Caterina was built, possibly used by visitors, who could not access the monastic church at that time, and which later served as a hospital for the poor. The kitchen also dates from the 13th century. To the east of the cloister is the large chapter house, of exceptional beauty; in the same direction are the library (formerly the writing hall) and the old granary, which has a similar structure and is now used as a library. The long dormitory, with slender diaphragm arches, was built on the upper part and is now also used as a library.

The abbacy of Ponç de Copons (1316-1348) led to an increase in building work in the monastery, such as the atrium in front of the entrance door to the monastery; the cubar (to make wine) to the west of the main cloister; and the rooms on the upper floor used as abbot's quarters. At the same time, the south wall of the church was modified to open the side chapels. The lantern tower also dates from this period. From 1369 onwards, the monastic complex was fortified, leaving a single entrance for the Royal Gate (with the arms of the crown sculpted on it), but these constructions lasted for a long time, so that they were not completed for another century.

Poblet became a royal pantheon, as well as a burial place for other personalities. Alfonso II, son of the founder, was the first monarch to be buried in the monastery (although there is a tombstone in Vilabertran (Alt Empordà), possibly with his entrails). King James I the Conqueror, seeing his death approaching, became a Cistercian monk in 1276, was one of the benefactors of the monastery and was also buried here. Peter the Ceremonious ordered the construction of the royal pantheon (when his predecessors were already buried in the monastic enclosure) and took care to arrange for the construction of the pantheon, in which the great sculptors of the time took part: Aloi de Montbrai and Jaume Cascalls. At that time, the decision was taken to place the tombs on lowered arches located between the columns of the transept.

Between the 14th and 15th centuries and by the will of King Martin the Humane, the royal palace was built by Arnau Bargués. In the mid-15th century, during the reign of Abbot Bartomeu Conill (1437-1458), the chapel of Sant Jordi was built outside the walled enclosure. The Golden Gate was built next to it shortly afterwards. In the time of Abbot Francesc Oliver de Boteller (1583-1598), the abbot's palace was built to the south of the monastic complex. In the 18th century, two constructions were built that broke the 14th-century wall: the new sacristy and the retired monks' quarters, while a gallery was built to link the monastery with the abbey palace, which was begun in the 16th century. In the 16th century, another walled enclosure was built, of which practically only the Prades gate remains.

In 1835, when the community had seventy monks, the monastery was suppressed and its members dispersed, leaving the place in the hands of plunderers, which particularly affected the royal pantheon. This situation was finally stopped by officially protecting the monastery. In 1940 the monastic function was recovered with the arrival of four monks from Italy. Today it has become a cultural and tourist destination, which in turn facilitates its maintenance. In 1991 it was declared a World Heritage Site by Unesco.

Affiliation of Poblet

According to Originum Cisterciensium (L. Janauschek, 1877)Grandselve Abbey (Tarn-et-Garonne) / 1145

Fontfroide Abbey (Aude) / 1146

Poblet Abbey (Conca de Barberà) / 1151

Monastery of Piedra (Zaragoza) / 1194

- ALEGRET, Adolfo (1904). El monasterio de Poblet. Barcelona: Salvat

- ALTISENT, Agustí (1974). Història de Poblet. Abadia de Poblet

- BALAGUER, Víctor (1885). Las ruinas de Poblet. Madrid: M. Tello

- BARRAQUER, Cayetano (1906). Las casas de religiosos en Cataluña durante el primer tercio del siglo XIX. Tomo I. Barcelona: Imprenta F.J. Altés

- BARRAQUER, Cayetano (1915). Los religiosos en Cataluña durante la primera mitad del siglo XIX. Vol. 1. Barcelona: Francisco J. Altés

- BASSEGODA, Joan (1983). Història de la restauració de Poblet. Abadia de Poblet

- BERTRAN Y GÜELL, F. (1944). El Real Monasterio de Santa Maria de Poblet. Barcelona: Montaner y Simón

- BLASI Y VALLESPINOSA, F. (1945). Monasterio de Poblet. Tesoro de fe y de arte. Barcelona: Librería Dalmau

- DOMÈNECH I MONTANER, Lluís (1920). Poblet. Barcelona: Thomas

- DOMÈNECH I MONTANER, Lluís (1925). Historia y arquitectura del monestir de Poblet. Barcelona: Montaner y Simon

- FINESTRES, Jayme (1746). Historia del Real Monasterio de Poblet. Barcelona: P. Campins

- FINESTRES, Jayme (1753-65). Historia del Real Monasterio de Poblet. Barcelona: P. Campins

- GONZALVO I BOU, Gener (2003). L’art gòtic a Catalunya. Arquitectura III. Dels palaus a les masies. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana

- GUITERT, Joaquín (1929). Real Monasterio de Poblet. Barcelona: Casa de la Caridad

- GUITERT, Ramon (1955). Historia del Real Monasterio de Poblet. Barcelona: Orbis

- MANOTE, Maria Rosa; TERÉS, Maria Rosa (2007). L’art gòtic a Catalunya. Escultura I. La configuració de l’estil. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana

- MANUSCRIT (1938, ed.). Cartulari de Poblet. Edició del manuscrit de Tarragona. Barcelona: I. Estudis Catalans

- MARÉS, Federico (1952). Las tumbas reales de los monarcas de Cataluña y Aragón en del monasterio de Santa María de Poblet. Barcelona: As. de Bibliófilos

- MARTINELL, César (1927). El monestir de Poblet. Barcelona: Barcino

- MASOLIVER, Alexandre (1995). Catalunya romànica. Vol. XXI, el Tarragonès, el Baix Camp, l’Alt Camp, el Priorat, la Conca de Barberà. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana

- MASOLIVER, Alexandre (2002). L’art gòtic a Catalunya. Arquitectura I. Catedrals, monestirs i altres edificis religiosos 1. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana

- MASOLIVER, Alexandre (2003). L’art gòtic a Catalunya. Arquitectura II. Catedrals, monestirs i altres edificis religiosos 2. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana

- MONTOLIU, Manuel de (1945). Leyendas de Poblet. Barcelona: Orbis

- MONTOLIU, Manuel de (1955). Llibre de Poblet. Barcelona: Selecta

- MORGADES S. O, Cist, Dom. Bernardo (1946). Guía del Real Monasterio Cisterciense de Santa Maria de Poblet. Barcelona

- MORGADES S. O, Cist, Dom. Bernardo (1948). Historia de Poblet. Barcelona

- PALAU, Antoni (1931). Guia de Poblet. Barcelona: I. Romana

- OLIVER, Jesús M.; i altres (2008). Cister, monestirs reials a la Catalunya Nova. Valls: Cossetània

- PALOMER, Mossen Josep (1928). La decadència de Poblet. Barcelona. Llib. Verdaguer

- SALAS RICOMÁ, Ramón (1893). Guía histórica y artística del Monasterio de Poblet. Tarragona: F. Arís e Hijo