The valley of Ripoll and other areas in this county and in Osona were repopulated from 879 onwards thanks to the initiative of Count Wilfred (Guifré) the Hairy, who undertook the reorganisation of a vast territory that extended beyond these counties. The monks and the network of monasteries that had begun shortly before on the northern slopes of the Pyrenees played an important role in this colonising task.

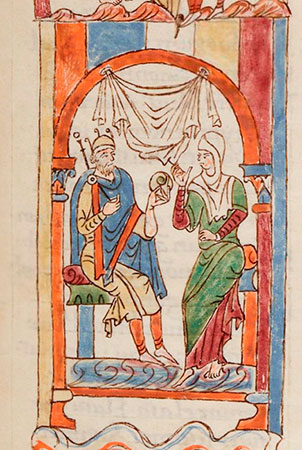

The monastery of Ripoll was a key element in this task. This house was founded by Count Guifré himself (who also founded the female monastery of Sant Joan de les Abadesses in the same context), probably in 879, and placed under the direction of Daguí, the first abbot, until then a priest in the church of Gréixer. The first mention of the monastic establishment in Ripoll dates to 880, in a donation in his favour. The community was probably established in provisional quarters and, in 888, Bishop Gotmar of Vic was able to consecrate the first church dedicated to Santa Maria. At that time the founders, Guifré and his wife Guinedilda, formalised a financial endowment and their son Radulf, born around 882-883, also joined the community, contributing other goods. Guifré died in 897 and was buried in the monastery.

Under the protection of the count, Ripoll developed and grew richer. In addition to the community church, two more were consecrated, which probably also served the needs of the population, servants, etc. who had gathered around it. The possessions of the monastery at this time were already important and extended to other regions, in addition to Ripollès itself. In this sense, it is worth mentioning the possessions received in the mountain of Montserrat. This economic development led to the construction of a new monastic church, which was consecrated in 935.

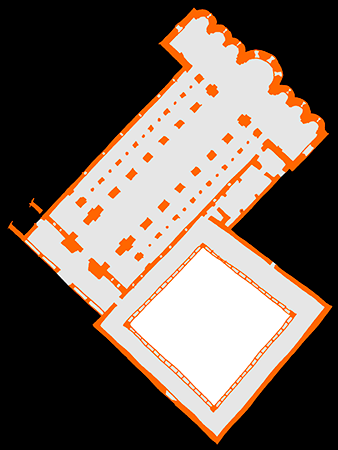

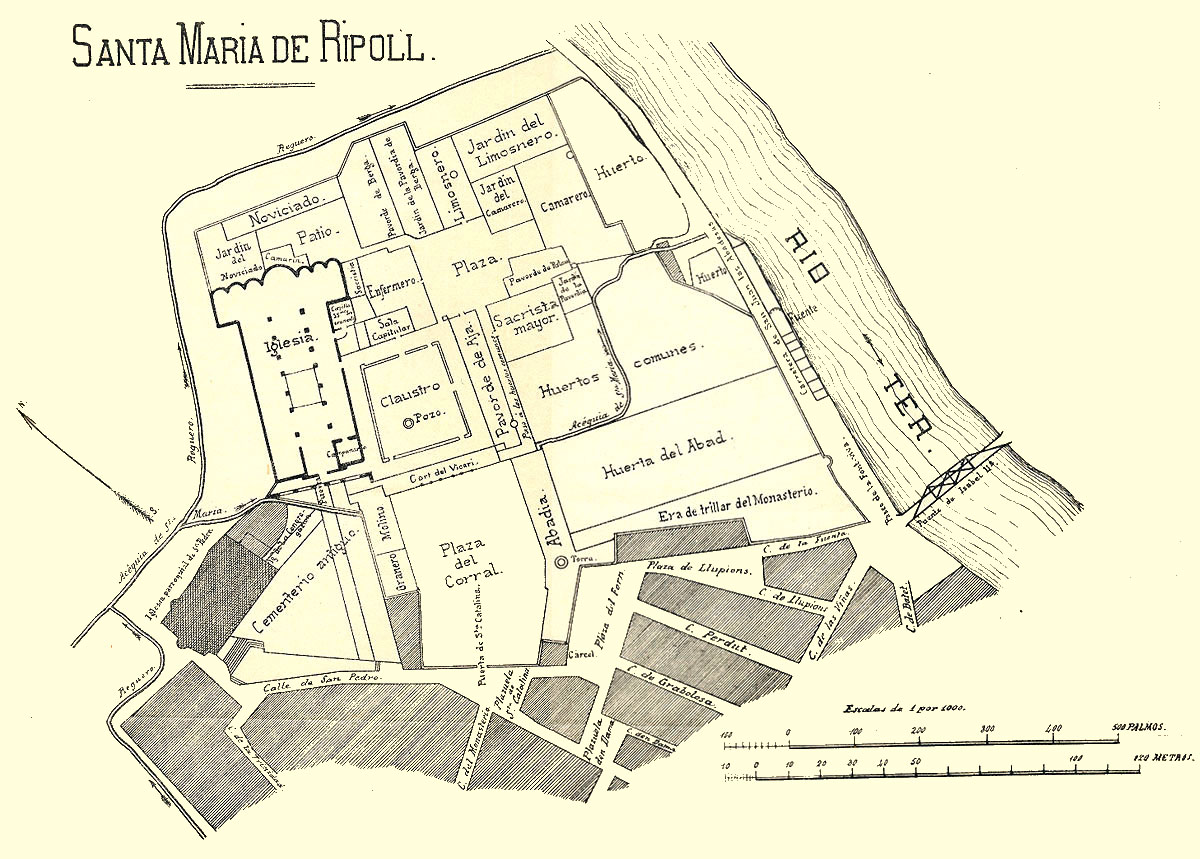

A third consecration was carried out shortly afterwards, in 977, the culmination of the construction work of Abbot Arnulf (the fourth abbot of Ripoll, who died in 970), which included a cloister and a wall to protect the complex. The church in Arnulf's time was similar to the present one and had five naves and five apses. Also, under the rule of Abbot Arnulf, Ripoll achieved the ratification of its possessions thanks to a papal bull from Pope Agapetus II (951) as well as its independence, which was from then on under papal protection. An important cultural development began also under the rule of Arnulf himself. The abbot sent copyists all over Europe to transcribe documents that would be of use to them, both in the strictly religious field and in the sciences. The Ripoll desk was at its peak of activity under Oliba's abbacy.

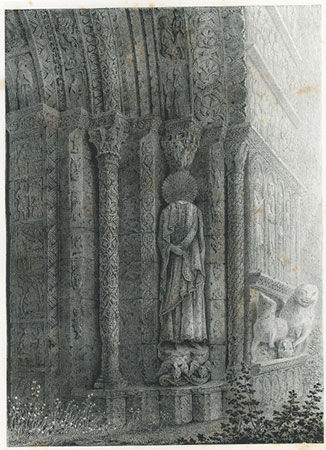

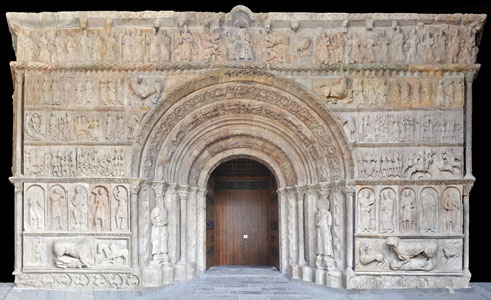

Oliba was from a noble family, son of Count Oliba Cabreta, he resigned his position and in 1003 he joined Ripoll. In 1008 he was elected abbot of this house and of Sant Miquel de Cuixà and from 1017 he was also bishop of Vic. He was involved in a wide range of political activities, the most important was the foundation of Montserrat, which remained under the direction of Ripoll until 1402. Under Oliba's abbacy, in 1032, a new consecration of the church took place, reflecting his building activity (also in Sant Pere de Vic and Sant Miquel de Cuixà) and which meant the total reconstruction of the building. It is this church, with important transformations, destructions and restorations, that is still preserved today. Ripoll served as the count's pantheon for many years.

Oliba’s death in 1046 marked the beginning of the abbey’s decline, leading to its merger with the abbey of Saint Victor of Marseille (Bouches-du-Rhône), which had become the head of several Catalonian monasteries. Simultaneously, he became involved in conflicts with the nearby monastery of Sant Joan de les Abadesses. Oliba also played a significant role in establishing dependent priories, including Sant Pere el Gros de Cervera, Santa Maria de Gualter, Santa Maria de Meià, Santa Maria del Coll de Panissars, Santa Maria de Banyeres, Sant Quintí de Mediona, and Sant Andreu de Tresponts, in addition to Montserrat.

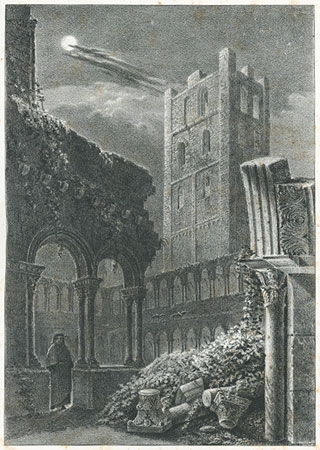

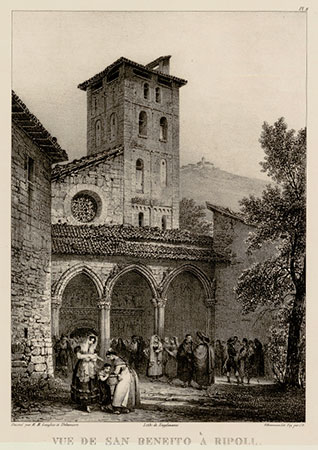

Following a period of tension, the abbey became independent from Marseille in 1172, which Saint Victor did not accept, leading to several lawsuits. Construction began on the present cloister. At the start of the 13th century, the monastery joined the Claustral Tarraconensis Congregation. The 14th century was marked by a decline in religious and economic life, worsened in 1290 when Ripoll’s residents looted the abbey, causing significant damage. The community lost many of its members, and its expenses and debts became overwhelming. In 1402, Montserrat was lost, and the community was further weakened by the plague and the earthquakes of 1428.

From 1461, an era of commendatory abbots began, primarily focused on collecting rents with little interest in reinvesting them into the monastery itself. Community life declined, with episodes of insubordination and periods without an abbot. The following centuries brought no improvement, and community life remained precarious. The beginning of the 19th century was marked by a first exclaustration (1820–1823). In 1830, the church was completely renovated, reduced from five to three naves. In 1835, definitive exclaustration occurred, followed by fire, destruction, and looting. Restoration efforts began in 1863, and in 1893, the church of Santa Maria was reconsecrated.

- ADELL, Joan-Albert (1987). Catalunya romànica. Vol. X. El Ripollès. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana

- ALIMBAU, Salvador; i altres (2009). Pantocràtor de Ripoll. La portada romànica del monestir de Santa Maria. Ajuntament de Ripoll

- ALIMBAU, Salvador; i altres (2018). Claustrum. Claustre medieval de Santa Maria de Ripoll. Ripoll: Maideu

- ARTIGAS RAMONEDA, José (1886). El monasterio de Santa Maria de Ripoll. Barcelona: F. Giró

- BARRAL, Xavier (1971). Els mosaics medievals de Ripoll i de Cuixà. Abadia de Poblet

- BOLÓS, Jordi; HURTADO, Víctor (2001). Atles del comtat d'Osona (798-993). Barcelona: R. Dalmau

- CABRERA GARRIDO, José María (1965). La conservación de la portada de Santa María de Ripoll. Ministerio de Educación Nacional

- COSTA, Xavier (2019). Paisatges monàstics. El monacat alt-medieval als comtats catalans (segles IX-X). Tesi doctoral. Universitat de Barcelona

- COSTA, Xavier (2022). Poder, religió i territori. Una nova mirada als orígens del monacat al Ripollès. Barcelona: Un. Barcelona

- CRIVILLÉ, Florenci (1987). La tomba del comte Guifré el Pelós en el monestir de Ripoll. Ajuntament de Ripoll

- GAVÍN, Josep M. (1978). Inventari d'esglésies. Vol. 4. Garrotxa - Ripollès. Barcelona: Artestudi Edicions

- JUNYENT, Eduard (1975). El monestir de Santa Maria de Ripoll. Ripoll: Junta d'Obra

- MASFERRER, José (1888). El monasterio de Ripoll. Ripoll: Balagué

- MUNDÓ, Anscari M. i altres (1992). Art i cultura als monestirs del Ripollès. Barcelona. P. Abadia de Montserrat

- ORDEIG I MATA, Ramon (2014). El monestir de Ripoll en el temps dels seus primers abats (anys 879-1008). Vic: EH

- PELLICER, José Mª (1888). Santa Maria del Monasterio de Ripoll. Mataró: F. Horta

- PIFERRER, P. (1843). Recuerdos y bellezas de España. Catalunya. Vol. 2. Barcelona

- SUREDA, Marc (2012). Una troballa recent: la Marededéu del Claustre de Ripoll. Taüll, núm. 35