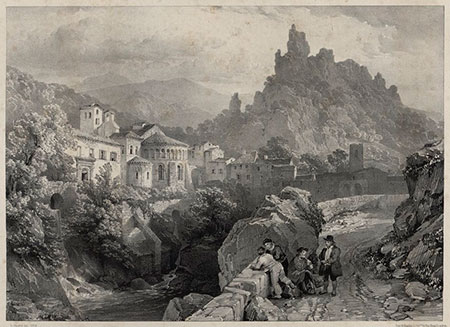

Abbey of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert

Saint-Sauveur / Abbaye de Gellone / M Gellonense

(Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, Hérault)

The origins of the Abbey of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert are linked to two historical figures: Benedict of Aniane (c. 750-821) and William I of Toulouse (768-812). Benedict abandoned his military career and service at Charlemagne’s court in 774 to enter monastic life. In 780, he retired to Aniane, very close to this site, where in 782 he founded the Monastery of Saint-Sauveur d’Aniane.

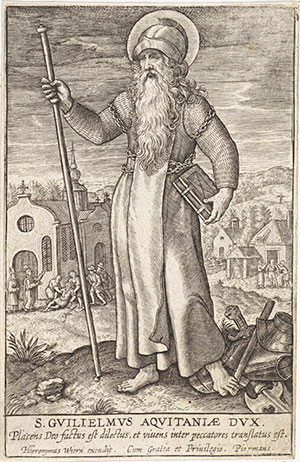

William, a relative of Charlemagne, was appointed Count of Toulouse and played a key role in reclaiming territories from the Saracens on both sides of the Pyrenees. In 804, he founded two monastic cells linked to Saint-Sauveur d’Aniane: one in Goudargues (Gard) and the second was this one at Gellone, later known as Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert. Following the example of his friend Benedict of Aniane, in 806 he abandoned court service and retired to the Gellone cell, where he died in 812. His figure gained prominence and was soon venerated as a saint, giving rise to a series of legends that became highly popular. This devotion was reinforced by the presence of a prized relic of the True Cross, which, according to tradition, was brought by the founder himself after receiving it from Charlemagne.

The monastery grew in importance and, thanks to its prosperity, managed to gain independence from Aniane. The first known abbot, Juliofred, is documented in a donation from 925. At the same time, devotion to Saint William continued to increase. Due to a fire that destroyed the abbey's archive, Aniane attempted to regain control, triggering a series of legal disputes that culminated in 1090 with Pope Urban II’s recognition of its independence. In 1138, the relics of Saint William were moved from the crypt to the main chapel, where they were preserved in a marble sarcophagus. The monastery’s vitality continued to grow, as did its wealth and prestige.

From 1465 onwards, the abbey was governed by commendatory abbots, mostly bishops of Lodève, who took advantage of the situation, as until then, the monastery enjoyed greater prestige than the bishopric itself and effective independence. As a result, religious life deteriorated, and the maintenance of buildings was neglected. In 1569, the abbey was sacked by the Huguenots, leading to the destruction of much of its furnishings. Subsequently, the community was forced to sell silver objects and reliquaries to cover defense expenses, as well as to relinquish the priory of Saint-Martin-de-Londres. The crisis persisted, and by 1624 the buildings, including the cloister, were in a state of ruin, except for the church.

In 1644, an attempt was made to revitalize monastic life with the arrival of new monks from the Congregation of Saint-Maur, who, in the 18th century, built new structures. This revival allowed the monastery to remain active until the French Revolution, when its properties were sold. In 1783, the last abbot and bishop of Lodève formally suppressed the abbey. As is typical for such buildings, expansions occurred over the course of history. No visible remains exist from the founding period in the early 9th century. The oldest remains are found in the crypt, rediscovered in 1962 beneath the presbytery, which likely belongs to a second pre-Romanesque construction from the 10th century.

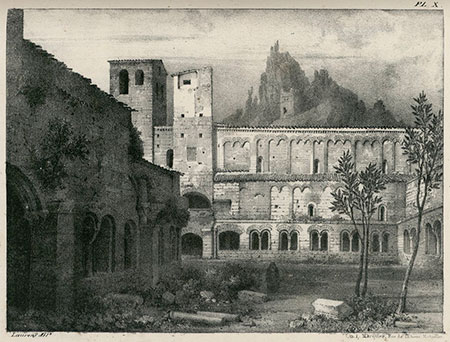

That structure probably suffered a fire, prompting the construction of a third building, essentially the one that has survived to this day. Notably, the large central apse, with a considerable width occupying the space of the three naves, stands out. This apse, reinforced with exterior buttresses, was built after the naves to replace an earlier pre-Romanesque one. The very narrow side naves ended in small apses beside the first central apse. Currently, two lateral apses open onto the transept. All these structures date, in different phases, to the 11th century.

The cloister had two floors: the lower one from the 11th century and the upper one from the 12th century. During this period, the upper floor was added to separate the monks from the many devotees visiting the abbey. From this floor, the monks could access the church, where they had reserved galleries, while the lower part remained accessible to the faithful. The second floor of the cloister has been completely lost, although part of it is partially reconstructed and preserved at The Cloisters in New York. The main facade is dominated by an imposing bell tower, at the base of which is a semicircular portal leading to the narthex, an addition intended to accommodate pilgrims and covered with an early pointed vault. In the 15th century, galleries were added to the transept to ensure the separation between the monastic community and visitors. The main altar dates from the 18th century.

Altar of Saint William

The Altar of Saint William is a marble work from the 12th century. On the front, to the left, a Christ in Majesty is depicted among the Evangelists, while on the right, a Crucifixion is shown, both scenes surrounded by exquisite vegetal ornamentation.

Altar of Saint William

Medieval Romanesque bridge over the Erau River, built based on an agreement between the monasteries of Gellone and Saint-Sauveur d’Aniane

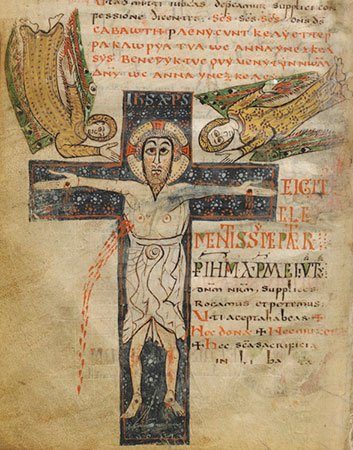

Eighth century manuscript, preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France

Copied in the diocese of Meaux (Île-de-France), it is believed to have been taken to this monastery by Saint William of Gellone

- ALAUS, Paul; i altres (1898). Cartulaires des abbayes d'Aniane et de Gellone. Cartulaire de Gellone. Montpellier: Marttel

- BONNERY, André (1989). Églises abbatiales carolingiennes, exemples du Languedoc-Roussillon. Les Cahiers de Saint-Michel de Cuxa, núm. 20. Prades: Abadia Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa

- CARRÉ, Pierre-Marie, dir. (2018). Saint-Guilhem-le-désert. Estrasburg: La Nuée Bleue

- COTTINEAU, Laurent-Henri (1939). Répertoire topo-bibliographique des abbayes et prieurés. Vol. 2. Mâcon: Protat

- DEVIC, Claude; i altres (1872). Histoire générale de Languedoc. Vol. 4: Tolosa de Ll.: Privat

- NOUGARET, Jean; i altres (1975). Languedoc roman. Zodiaque: La Pierre-qui-Vire

- RENOUVIER, Jules (1840). Monumens de quelques anciens diocèses de Bas-Languedoc. Montpellier: Picot

- SAINT-MAUR, Congregació de (1739). Gallia Christiana in provincias ecclesiasticas distributa. Vol. 6. París: Typographia Regia