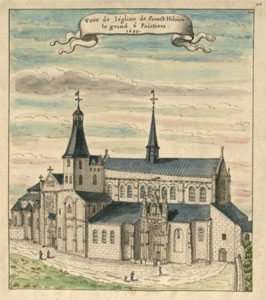

Collegiate Church of Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand in Poitiers

Chapitre Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand / S Hilarius Magnus

(Poitiers, Vienne)

According to tradition, based on hagiographic texts, around the year 363 Saint Hilary, bishop of Poitiers, built a chapel and a house for the clerics in charge of it, on land he owned. The site was dedicated to the martyrs John and Paul (4th century) and became the burial place, first for his wife and daughter, and later for Hilary himself, in the year 367.

After being destroyed during the invasions of the 5th century, the church was rebuilt at the beginning of the following century with the support of Clovis I (466–511), after a miraculous event that took place in 507. It was then placed under the patronage of Saint Hilary. The site was mentioned by Gregory of Tours (c. 538–594) following his visit. During the 8th and 9th centuries, the church suffered from the unrest of the time, including Islamic and Norman invasions, which forced the community responsible for the place to take refuge in Le Puy-en-Velay, bringing the relics with them. Despite this, a charter issued by Pepin the Short in 769 confirmed the property of the abbey, suggesting that it remained with some activity.

At the end of the 8th century, some members of the community moved to the Abbey of Nouaillé (Vienne), adopting the Rule of Saint Benedict. That monastery had been founded with the participation of Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand. In the 9th century, a new reconstruction was launched, with Queen Emma of Normandy († 1052), wife of Æthelred the Unready († 1016), supporting the works until 1044, when she was removed from court. Later, Agnes of Burgundy († 1068), wife of William V of Aquitaine the Great († 1030), completed most of the building, and the church was solemnly consecrated in 1049.

In the mid-10th century, William III, Duke of Aquitaine († 963), appointed his brother Ebles as abbot of the house. In 1074, Pope Gregory VII placed Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand under the protection of the Holy See. The canonical community was originally monastic in nature, living under a communal rule, but likely from its 10th-century restoration, it became a secular chapter of canons. The office of abbot, initially elected by the community, came to be appointed by the count’s household or the bishop of Poitiers.

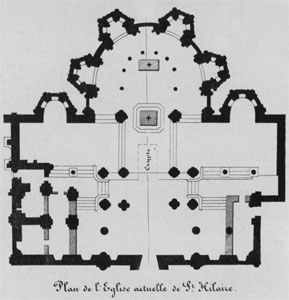

The 11th- and 12th-century church had a distinctive floor plan: a central nave flanked by a double row of columns forming a corridor, followed by side aisles—two on each side—since the vault was supported by central columns. That building underwent Gothic modifications and was fortified during the Wars of Religion. However, it suffered extensive damage, including the loss of furniture and relics of the titular saint, which disappeared during the sack of the church by the Huguenots. As a result, the chapter requested a relic to be returned from Le Puy, where some had been preserved since the 9th century invasions.

* Old construction / * 19th century reconstruction / * Lost part

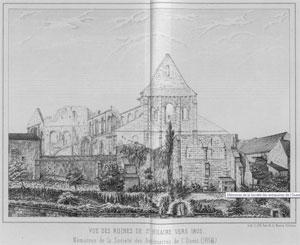

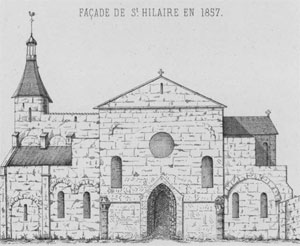

In addition to other interventions in the 17th and 18th centuries, the church was affected by the Revolution, during which it was sold. In the early 19th century, demolition began to reuse the building materials, but this was eventually halted and the church was turned into a parish. The reduced building included the apse and its chapels, the transept, and a very short nave. Later, the restored structure underwent new works: between 1870 and 1884, the nave was partially rebuilt, resulting in the current church, somewhat shorter than the medieval one. Over time, various additions and modifications were made to the side chapels, the bell tower, and other architectural elements.

- AUBERT, Marcel (1952). Saint-Hilaire de Poitiers. Congrès archéologique de France. 109 ss. Poitiers. Société française d'archéologie. Paris

- BARBIER, Paul (1887). Vie de Saint Hilaire, évêque de Poitiers, docteur et père de l'église. París: Poussielgue

- BEAUNIER, Dom (1910). Abbayes et prieurés de l'ancienne France. Vol. 3: Auch, Bordeaux. Abbaye de Ligugé

- BOURALIÈRE, A. de la (1890). L’église Saint-Hilaire le Grand. Paysages et monuments du Poitou, vol. I. París: S. Imprimeries R.

- CAMUS, Marie-Thérèse (1982). La reconstruction de Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand de Poitiers à l'époque romane. Cahiers de civilisation médiévale, núm. 98

- LABANDE-MAIFERT, Yvonne (1957). Poitou roman. La nuit des temps, 5. Zodiaque

- LEFÈVRE-PONTALIS, M. (1913). Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand. Congrès archéologique de France. LXXIX session tenue a Angoulême. Paris / Caen: Picard / Delesques

- LONGUEMAR, M de. (1857). Essai historique sur l’église collégiale de Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand de Poitiers. Mémoires de la Société des antiquaires de l'Ouest. Poitiers / Paris: Derache

- MAILLARD, Élisa (1934). Le problème de la reconstruction de Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand au XIe siècle. Bulletin de la Société des antiquaires de l'Ouest. Poitiers

- MARCHEGAY, Paul; i altres; ed. (1869). Chronique de Saint-Maixent. Chroniques des églises d'Anjou. París: Renouard

- RÉDET, Louis (1848-57). Documents pour l'histoire de Saint-Hilaire de Poitiers. Mémoires de la Société des antiquaires de l'Ouest

- SAINT-MAUR, Congregació de (1720). Gallia Christiana in provincias ecclesiasticas distributa. Vol. 2. París: Typographia Regia

- WEISE G. (1953). L'énigme de l'église Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand de Poitiers. Bulletin Monumental, vol. 111