Monastery of Sant Cugat

Octavianum Monastery / Sancti Cucuphati

Sant Cugat del Vallès, Vallès Occidental)

The origins of the monastery of Sant Cugat go back a long way, with some dating it to the 6th century, although there is no documented evidence of its existence until 878, thanks to a precept of Louis the Stammerer given to Bishop Frodoí of Barcelona.

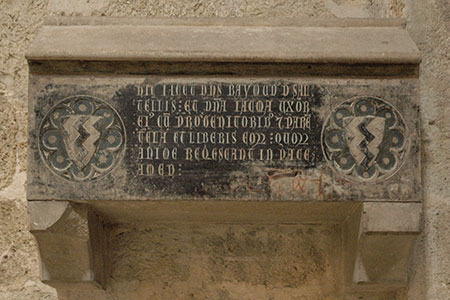

This site had previously been occupied by a Roman settlement (the Castrum Octavianum), where from the 4th century an intense religious activity began to develop, centred on the martyrium dedicated to Saint Cugat (Cucuphas). According to tradition, he had died there, a victim of Diocletian's persecutions. Several buildings and perhaps a first community grew up around his tomb until it was destroyed by the Saracen invasion in 717. It is known that the site was recovered in 801 and possibly the community was re-established, a fact that cannot be determined with certainty until 878. At that time the Visigoth constructions were used, some of which can still be seen in the cloister.

There are ancient chroniclers of the same monastery who mention a first abbot: Donadeu, who governed the place between 794 and 801, but this version does not seem sustainable. It is possible that it was initially a canonical community linked to the see of Barcelona and that it gradually adapted to the rule of Saint Benedict, according to its own organisation, independent of the bishopric. The first truly documented abbot was Ostofred (878-895). Abbot Gotmar (944-c954) was also bishop of Girona, and as such was involved in the foundation of Sant Pere de Camprodon. In 985 the monastery of Sant Cugat was attacked by Almanzor on his entry into Barcelona. The place was destroyed, and several monks died, among them the abbot Joan (973-985).

However, the place quickly became a religious and power centre of the first order. Its properties extended over the whole bishopric and were considerable. The monastery played an important role in the defence and repopulation of the territory, and the abbot Odó (986-1010) even took part personally in a military expedition, in which he died. This abbot initiated the construction of a new Romanesque church. In 986 it is recorded that the cell of Sant Genís and Santa Eulàlia de Tapioles depended on it. In 1079 there is evidence of the discovery of the body of Saint Cugat. The presence of the relics intensified his devotion.

In 1089, taking advantage of the fact that the death of the abbot had left a vacancy, the monastery became dependent on Saint-Pons-de-Thomières, in Languedoc, along with other Catalan monasteries. This situation did not last long. In 1091 its independence was restored. Its importance at this time is clear if we take into account the monasteries that depended on it: Sant Llorenç de Munt, Santa Cecília de Montserrat, Sant Salvador de Breda, Sant Pau del Camp a Barcelona, Santa Maria del Coll and Sant Pere de Clarà. Its privileged location is evident in the architectural work that was carried out and the important desk that was developed within its walls, where an important bibliographic collection was generated and grouped together, of which important witnesses are still preserved.

This period of prosperity lasted, with few periods of decadence, until the end of the 13th century. The 14th century was marked by a crisis, which even had such singular episodes as the murder of Abbot Arnau Ramon de Biure (1348- 1350) in the altar itself, due to a testamentary dispute. The Catalan Civil War hit the monastery hard, and the abbot Antoni Alemany (1461-1471) was imprisoned and died while being sent into exile. The decline in income was also very important. The monks lost the power to elect the abbots and in 1471 an era of commendatory abbots began, with little interest in monastic life and the development of the place. From 1561 the abbots were elected by royal appointment.

In the second half of the 18th century, a certain revival took place, allowing the monastery to undertake its last works and renovations. But the following century saw the end of the community: in 1820 it was dissolved, and its properties were put up for auction, while the church became a parish church. In 1823, the monks returned, until 1835, when the community was dissolved for good, losing all its assets. The monastery passed into the hands of the State and fell victim to looting. In 1844, the town council took over the use of the monastery, while the church took on the functions of a parish. In the second half of the 19th century, restoration work began, followed by archaeological excavations.

The oldest structures are the archaeological remains of the cloister courtyard, from the pre-Romanesque era. Subsequently, new buildings were erected (11th century) of which there are no apparent remains. The monastery was renovated in the second half of the 12th century, when the current cloister was erected, and the construction of a new church began. The work was carried out very slowly, starting with the chancel. Then the renovation stopped and did not continue until the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century, at the height of the Gothic period. The splendid rose window on the façade dates from 1340.

The cloister

The cloister is quadrangular in plan, each of its four wings is divided into three bays by two pilasters. Each section consists of six pairs of columns with capitals, those at the ends of which are attached to the pillars.

- ABADAL, Ramon d’ (2007). Catalunya Carolíngia. Vol. II. Els diplomes carolingis a Catalunya. 1. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans

- ADELL, Joan Albert (2002). L’art gòtic a Catalunya. Arquitectura I. Catedrals, monestirs i altres edificis religiosos 1. Enciclopèdia Catalana. Barcelona

- ADELL, Joan Albert (2003). L’art gòtic a Catalunya. Arquitectura II. Catedrals, monestirs i altres edificis religiosos 2. Enciclopèdia Catalana. Barcelona

- AMBRÓS MONSONÍS, Jordi (1980). El monestir de Sant Cugat del Vallès. Vilassar: Oikos-Tau

- ARTIGUES, Pere Ll. (2003). El monestir de Sant Cugat del Vallès. L’evolució arquitectònica a partir de l’arqueologia. Actes del II Congrés d'arqueologia medieval i moderna de Catalunya. ACRAM

- ARTIGUES, Pere Lluís; i altres (1997). La fortalesa romana, la basílica i el monestir de Sant Cugat del Vallès o d’Octavià (Catalunya). Les excavacions de 1993-1995. Annals de l’Institut d’Estudis Gironins, núm. 37

- BALAGUER, Víctor (1851). Los frailes y sus conventos. Vol. 2. Llorens Hnos.

- BALTRUSAITIS, Jurgis (1931). Les chapiteaux de Sant Cugat del Vallès. París: E. Leroux

- BARRAQUER Y ROVIRALTA, Cayetano (1906). Las casas de religiosos en Cataluña durante el primer tercio del siglo XIX. Vol. 1. Barcelona: Imp. Fco. J. Altés

- BLASCO, Mònica (1999). Sant Cugat del Vallès, la configuració del monestir i els seus precedents. Catalunya a l'època carolíngia. Diputació de Barcelona

- BOTO, Gerardo (2007). Monasterios catalanes en el siglo XI. Los espacios eclesiásticos de Oliba. Monasteria et territoria. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

- BOU PALMES, Xavier (1988). El monestir de Sant Cugat en el segle X. Sant Cugat del Vallès: Estudis Santcugatencs

- COMPTE, Efrem E. (2009). El costumari del monestir de Sant Cugat del Vallès. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans

- COSTA, Xavier (2019). Paisatges monàstics. El monacat alt-medieval als comtats catalans (segles IX-X). Tesi doctoral. Universitat de Barcelona

- FONTANALS, Reis; i altres (2000). XLII Assemblea Intercomarcal d'Estudiosos. Sant Cugat del Vallès. Barcelona: Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya

- GRIERA, Antoni (1969). Guía descriptiva histórica y artística del monasterio de San Cugat del Vallés. Barclona: La Polígrafa

- GUASCH DALMAU, David (2001). L’activitat repobladora del monestir de Sant Cugat del Vallès vers el Penedès al darrer quart dels segle X i primer de l’XI. Miscel·lània penedesenca, vol. 26

- GUÉRIN, Paul (1888). Les Petits Bollandistes. Vies des saints. Vol. 9. París: Bloud et Barral

- LLORENS, Martí (2002). Abaciologi del Reial Monestir de Sant Cugat del Vallès. Ajuntament de Sant Cugat

- MOXÓ, Benet (1790). Memorias historicas del real monasterio de San Cucufate del Valles. Barcelona: Surià

- MOYA OLLER, Anna (2017). Ascetisme i monacat tardoantic a la tarraconense (ss. IV-VII). Una aproximació sociocultural i arqueològica. Tesi Doctoral. Tarragona: Universitat Rovira i Virgili

- PERAY Y MARCH, José de (1931). Sant Cugat del Vallès. Su descripción y su historia. Barcelona: Casa de la Caridad

- PUIGFERRAT, Carles (1991). Sant Cugat del Vallès. Catalunya romànica. Vol. XVIII. El Vallès occidental, el Vallès Oriental. Enciclopèdia Catalana. Barcelona

- RIUS, José (1945-1957). Cartulario de “Sant Cugat” del Vallés. Vol. I, II i III. Barcelona: CSIC

- RODRÍGUEZ, Alba; i altres (2002). La butlla de Silvestre II al Monestir de Sant Cugat. Commemoració del Mil·lenari (1002-2002). Ajuntament de Sant Cugat

- ROGENT, Elies (1881). Sant Cugat del Vallès. Apuntes histórico críticos. Barcelona: La Academia

- ROVIRA I SOLÀ, Manuel (1980). Notes documentals sobre alguns efectes de la presa de Barcelona per al-Mansur (985). Acta historica et archaeologica mediaevalia, núm. 1

- TORTOSA, Joan (1998). El claustre de Sant Cugat del Vallès. Més enllà de les formes. Sabadell: Ausa

- VIVÓ I GILI, Pere (2006). El Monestir de Sant Cugat a partir dels monjos i enllà... dades per a la història. Barcelona: Mediterrània

- VIVÓ I GILI, Pere (2008). L'església del monestir de Sant Cugat. Barcelona: Mediterrània

- Enllaç ↗ : El monestir de Sant Cugat

- Enllaç ↗ : El museu del monestir