It is believed that the Monastery of San Xulián de Moraime originated from a group of hermits who gathered as a community in this location, an establishment that later evolved into this Benedictine monastery. Moraime was first documented in 1095, when the Monastery of San Juan de Borneiro was annexed to it.

In 1119, Alfonso VII of León (1105–1157), who had sought refuge in this monastery for several years, granted it a privilege that included the creation of a territory under its jurisdiction, as well as providing aid for the reconstruction of the monastery, which had been destroyed during a Saracen raid. During this restoration, the original church was completely rebuilt. Toward the end of his life, the monarch made further donations to Moraime. In the future, the monastery would continue to benefit from similar initiatives promoted by his successors to the throne.

Ferdinand III the Saint (1199-1252) confirmed the series of previous donations. Later, other confirmations were issued up until the early 15th century, when the monastery began to lose control of its territory, which gradually passed into the hands of the local nobility. At the end of the same century, the monastery was reformed in terms of religious observance, despite opposition from its own community. In 1494, it came under the jurisdiction of San Martiño Pinario as a priory, and in 1499, it was incorporated into the Congregation of San Benito de Valladolid. In addition to several raids by pirates during the modern era, the monastery was also a victim of the Peninsular War in the 19th century and, ultimately, it was suppressed in 1835 due to the Spanish confiscation laws.

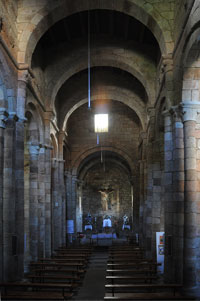

The Romanesque church from the 12th century is still preserved, albeit with some modifications. It has a basilica floor plan with three naves and three apses. The central apse, however, is now rectangular in shape, the result of a reconstruction that caused it to lose its original Romanesque features. The main western portal features a tympanum with seven figures, and the surrounding archivolts are also decorated with sculptural reliefs, as are the side columns, which depict additional figures. A second portal, located on the southern façade, is centred around a tympanum depicting the Last Supper. The other elements of this portal are also sculpted, although they are harder to interpret due to the weathering of the stone.

- BENLLOCH DEL RÍO, José Enrique (2012). Acotacións históricas de Moraime. Nalgures, núm. 8

- BENLLOCH DEL RÍO, José Enrique (2015). La documentación medieval del priorato de Moraime (I). Nalgures, núm. 11

- BENLLOCH DEL RÍO, José Enrique (2020). La documentación medieval del priorato de Moraime (II): Privilegio del rey Pedro I al monasterio de Moraime en 1351. Nalgures, núm. 17

- FERNÁNDEZ DE VIANA, José Ignacio (1992). Nuevos documentos del monasterio de San Xiao de Moraime. Historia. Instituciones. Documentos, núm. 19

- FRANCO TABOADA, José Antonio (2009). Igrexas dos mosteiros e conventos de Galicia. Xunta de Galicia

- FREIRE CAMANIEL, José (1998). El monacato gallego en la alta edad media, vol. II. La Corunya: Fund. Pedro Barrié de la Maza

- PÉREZ GONZÁLEZ, José María; dir. (2013). Enciclopedia del románico en Galicia. A Coruña. Aguilar de Campoo: Fundación Santa María la Real

- PÉREZ RODRÍGUEZ, Francisco Javier (2008). Mosteiros de Galicia na Idade Media. Ourense: Deputación Provincial de Ourense

- SÁ BRAVO, Hipólito de (1972). El monacato en Galicia. Vol. 1. La Corunya: Librigal