The Benedictine monastery of San Salvador de Celanova was founded by Rosendo Gutiérrez (Saint Rudesind, 907–977), Bishop of Dume-Braga (Portugal). Rosendo came from a noble family; his brother, Froila, received in 935 the lands that the following year he would dedicate to the monastery’s foundation. The monastery was already operational by 938, as evidenced by the first documented donation in its favor, made by Ilduara, Rosendo’s mother.

Initially, the monastery of Celanova maintained a relationship with that of Santo Estevo de Ribas de Sil, from which the first monastic community originated. Among those monks was Fránquila, appointed by Rosendo as the first abbot. In 959, after Fránquila’s death, Rosendo personally assumed the position of abbot until his own death in 977. During the early 12th century, the monastery adopted the Rule of Saint Benedict and came under the jurisdiction of the Bishopric of Ourense, which led to disputes over maintaining its independence.

These conflicts were not fully resolved until 1221, when the monastery became part of the Diocese of Ourense while retaining jurisdiction over several parishes. Over time, with the support of the monarchy, it became an influential and powerful institution, with several dependent priories (including Santa Comba de Bande, San Pedro de Rocas, San Salvador de Coruxo, San Pedro de la Nave, and Santa Comba de Naves) and a remarkable heritage. After a period under commendatory abbots, the monastery was incorporated into the Congregation of San Benito de Valladolid in 1506, giving it a new impetus.

This is reflected in the constructions undertaken in subsequent centuries, such as the 17th-century Baroque church, which replaced the earlier Romanesque building. The monastery’s monastic life came to an end with the expropriation of 1835. The church became a parish, while the other monastic buildings were repurposed for various uses, including as a barracks, prison, town hall, and schools. Despite this, the monastic complex has been remarkably well preserved, both in terms of its structures and furnishings.

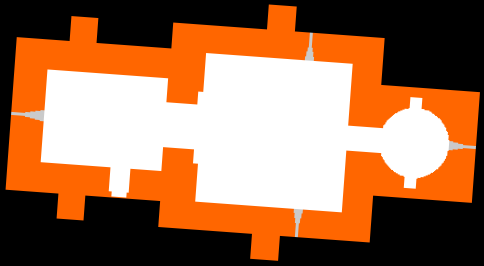

From the initial phase, the chapel of San Miguel stands out, a construction from the 10th century, according to an inscription, was dedicated to the memory of Froila, the founder’s brother. The role of this chapel within the monastic complex is not entirely clear, but it seems to have been significant enough to be preserved through the monastery’s later reconstructions. The church was entirely rebuilt during the second half of the 17th century. Although a new choir was added, the upper choir from the late 15th century is also preserved. The monastic buildings are arranged around two cloisters.

- BARRAL RIVADULLA, Mª Dolores (2009). Diálogos artísticos en el siglo X. La imagen arquitectónica de San Miguel de Celanova. Cuadernos de estudios gallegos, núm. 56

- CARRIEDO, Manuel (2009). San Rosendo, la Familia Real y los orígenes de Celanova. Rudesindus, núm. 5

- FERNÁNDEZ CASTIÑEIRAS, Enrique; i altres; dir. (2007). Arte Benedictino en los caminos de Santiago. Opus Monasticorum II. Xunta de Galicia

- FREIRE CAMANIEL, José (1998). El monacato gallego en la alta edad media, vol. II. La Corunya: Fund. Pedro Barrié de la Maza

- LÓPEZ QUIROGA, Jorge (2007). Monasteria et territoria en la Galicia interior en torno al año mil. El monasterio de San Salvador de Celanova. Actas del III Encuentro Internacional e Interdisciplinar sobre la alta Edad Media en la Península Ibérica

- PÉREZ RODRÍGUEZ, Francisco Javier (2008). Mosteiros de Galicia na Idade Media. Ourense: Deputación Provincial de Ourense

- SÁ BRAVO, Hipólito de (1972). El monacato en Galicia. Vol. 2. La Corunya: Librigal

- SÁ BRAVO, Hipólito de (1982). El monasterio de Celanova. Lleó: Everest

- ZARAGOZA PASCUAL, Ernesto (2000). Abadologio del monasterio de San Salvador de Celanova (Siglos X-XIX). Compostellanum, vol. 45/1-2