Only a few remains of the Abbey of Grandmont have survived, which in its time was the mother house of the homonymous order that expanded during the Middle Ages from this location. The origin of the order can be traced to the figure of Stephen of Thiers (Stephen of Muret or Stephen de Grandmont), son of the Viscount of Thiers, who was born in that city in 1046 and travelled to Italy at a young age. After a stay in Rome, he returned to Auvergne and, in 1076, withdrew to lead an eremitic life in an isolated place, in Muret, near Limoges.

After a period of solitary life, he began to be known by the inhabitants of the region, and soon other hermits joined him, eventually forming a cenobitic community. Thanks to Stephen’s growing popularity, the establishment received support and protection from the nobility, and in 1112 a church was consecrated at the site. Stephen of Thiers died in Muret in 1124. His initiative is part of the spiritual movements of the time, which sought a return to stricter cenobitic practices and a life withdrawn from the world—movements from which also emerged other orders such as the Camaldolese, the Carthusians, or the Grandmont order itself.

From this first foundation, various hermit centres were established in the surrounding area, which eventually led to the creation of the Grandmont order, characterised by a strict internal rule or code of conduct. The Holy See recognised the order’s activity and progressively approved the different elements of its rule, also granting it the privilege of exemption. The order imposed a rigorous limitation on the possession of property outside the monastic precinct: the monasteries sustained themselves through their own means and by charity. The creation of a female branch was not permitted either.

Reliquary of Stephen of Muret

from the Abbey of Grandmont

Now in Saint-Sylvestre (Haute-Vienne)

Photo by Mossot, on Wikimedia

L’any 1125, ja mort el fundador, la comunitat es traslladà al lloc pròxim de Grandmont. El 1166 es conclogué la construcció d’una nova església, que fou consagrada amb gran solemnitat, en presència de diversos bisbes i abats d’altres monestirs. Els grandmontesos s’expandiren ràpidament pels territoris de l’actual França, on centraren la seva activitat, i arribaren també a la península Ibèrica, on establiren dues cases a Navarra: una a Tudela i una altra a Estella.

In 1189, Stephen of Grandmont was canonised, and to commemorate the occasion, a new altar was built, decorated with splendid enamels. This altar, paradoxically contrary to the spirit of poverty advocated by the order, still survives in part. It housed, in addition to the relics of Saint Stephen, other reliquaries that were later added, altering the original structure. Today, only one of these pieces remains, currently in Ambazac, along with two enamelled plaques preserved at the Cluny Museum in Paris.

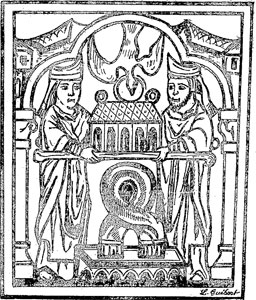

Two bishops with the chasse of Saint Stephen of Muret

Drawing of a miniature from Speculum Grandimontis

Published in Histoire de l’abbaye de Grandmont

After a period of some decline, Pope John XXII initiated a reform in 1317, granting the status of abbey to what had until then been the priory of Grandmont. He also reduced the number of dependent priories to thirty-nine and grouped the numerous cells that existed until that time. Furthermore, he established a system for the election of the abbot of Grandmont and the priors of the various dependent houses. In 1363, the Abbey of Grandmont suffered the effects of the Hundred Years’ War, and many of its priories also endured episodes of destruction.

From 1471 onward, the abbey was governed by commendatory abbots. That year, Charles II of Bourbon was appointed abbot; among other titles, he was also Archbishop of Lyon, although he never visited Grandmont. This system of commendation remained in place until 1563, when the monks regained the right to elect their abbot. In 1770, an attempt was made to reform the observance of the order’s houses, but resistance from certain sectors led to its definitive suppression in 1772, which was formalised by a papal bull.

Monk of Grandmont, according to

Histoire des ordres monastiques religieux et militaires et des congrégations

By 1788, the monastery buildings—rebuilt on medieval foundations—were already in ruins. Most of the movable goods were lost or dispersed. Today, only a few remnants remain at Grandmont, many of them uncovered in recent years during archaeological excavations and studies.

Now in the church of Ambazac (Haute-Vienne)

- AUBERT, R. (1986). Dictionnaire d'histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques. Vol. 21. París: Letouzey et Ané

- BEAUNIER, Dom (1912). Abbayes et prieurés de l'ancienne France. Vol. 5. Bourges. Abbaye de Ligugé

- BRESSON, Gilles (2000). Monastères de Grandmont. Guide d'histoire et de visite. Le Château d’Olonne: Orbestier

- DU BOYS, Auguste (1855). Inventaire des châsses, reliques, croix, reliquaires, coffres, calices et autre argenterie de l'église de Grandmont. Bulletin de la Société archéologique et historique du Limousin, vol. VI

- FRANÇOIS-SOUCHAL, Geneviève (1962-64). Les émaux de Grandmont au XIIe siècle. Bulletin Monumental, vol. 120-122

- GABORIT, Jean-René (1976). L'autel majeur de Grandmont. Cahiers de civilisation médiévale, núm. 75

- GUIBERT, Louis (1877). Destruction de l’ordre et de l’abbaye de Grandmont. Paris / Limoges: Champion / Ducourtieux

- HÉLYOT, Pierre (1718). Histoire des ordres monastiques religieux et militaires. Vol. 7. París: Coignard

- LECLER, A. (1907). La châsse d’Ambazac. Bulletin de la Société archéologique et historique du Limousin, vol. 57. Limoges: Ducourtieux

- LECLER, A. (1907-1911). Histoire de l’abbaye de Grandmont. Bulletin de la Société archéologique et historique du Limousin. Limoges: Ducourtieux

- PELLICCIA, Guerrino; dir. i altres (1977). Dizionario degli istituti di perfezione. Vol. 4. Roma: Ed. Paoline

- RACINET, Philippe (2015). Abbaye chef d’ordre de Grandmont. Archéologie médiévale, núm. 45

- RACINET, Philippe (2019). Saint-Sylvestre (Haute-Vienne). Abbaye de Grandmont. Archéologie médiévale, núm. 49

- SAINT-MAUR, Congregació de (1720). Gallia Christiana in provincias ecclesiasticas distributa. Vol. 2. París: Typographia Regia