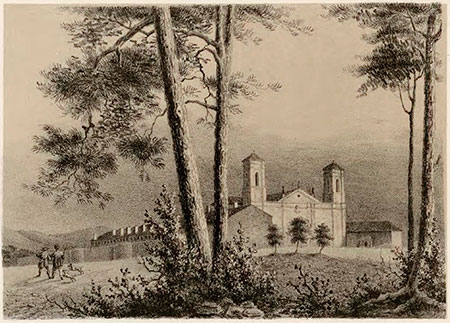

Monastery of San Juan de la Peña

Monastery of Saints Julian and Basilissa / Sancto Ioanni de Pinna / Penna

(Jaca, Huesca)

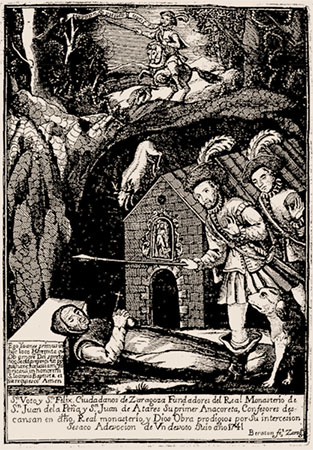

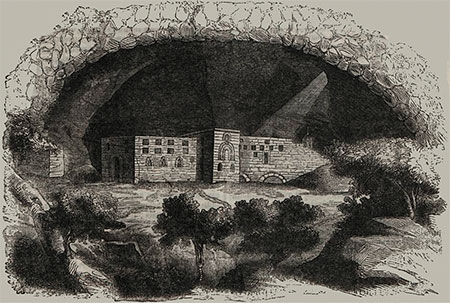

The monastery of San Juan de la Peña has its origin in a small hermitage located in a sheltered cave. A legend, which dates to pre-Islamic times, tells the story of the accidental discovery of the body of the anchorite Juan de Atarés, who had not been buried because of his isolation. The people who found him stayed there, which allowed the hermitage to continue.

In the counts' era, the primitive hermitage evolved into a monastic centre under the patronage of Saints Julian and Basilissa. During the first half of the 10th century, a small church with two naves was built, dug into the rock that sheltered it. There was practically no news of this place until the time of Sancho III the Great (who ruled between 1004 and 1035), when a new impetus was given to monastic life, which in 1028 adopted the Benedictine rule. The centre was endowed with revenues for its subsistence and a long series of small monastic establishments in the surrounding area came to depend on it. In 1071, the monastery was ruled directly from Rome, then under Alexander II's papacy, which confirmed its possessions, while at the same time pitting it against the bishopric of Jaca.

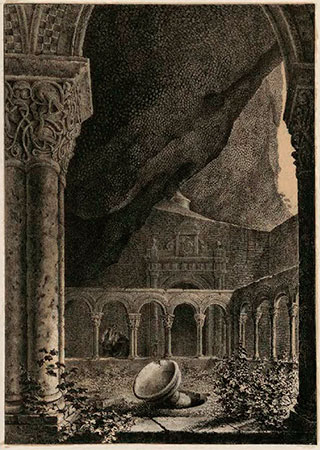

This new situation made the monastery an influential and powerful centre. This wealth made it possible to extend the buildings, which had proved to be insufficient. Due to the limited space available, it was decided to extend the building by adding a storey on top of the old buildings. The new, enlarged church was consecrated in 1094. It must be said that many of the buildings that once existed have been lost. For a time, this monastery was used as a royal pantheon. Around the 12th (and possibly the 13th) century, the cloister was built, a magnificent ensemble that has been partially preserved and was executed by different workshops. In 1080 it was given the church of Santa María de Iguácel, where a priory was founded.

A series of events led to the beginning of the decline of this house. First, disagreements with the authorities, and then the relaxation of customs in the monastery itself, including the sale of possessions and the abandonment of the monastery by some of the members of the community. The situation was aggravated by the high level of indebtedness and due to fortuitous events, a fire broke out in 1375. This type of incident was repeated in 1494 and again in 1675. To all these circumstances must be added the very nature of the building itself, in an unsuitable location, under a poorly oriented rock and with humidity, which meant that it had to be continually repaired.

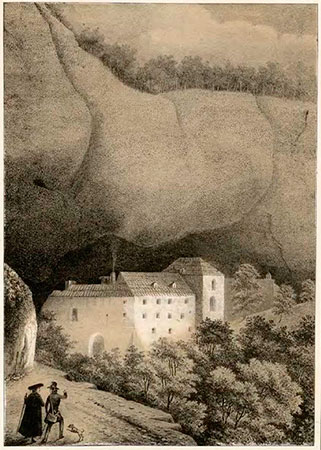

Due to the fire of 1675, the site was rendered uninhabitable. The community was forced to move to the meadows above and prepare a new building. This relocation was formalised in 1682, although the work had not been completed due to financial difficulties. The Peninsular War led to another fire (1809) and the flight of the monks, who were not able to regularise the community to a minimum until 1815, after which it suffered the period of the Liberal Triennium. The disentailment of 1835 put a definitive end to monastic life. Although the new monastery was protected, the complex gradually deteriorated and it was not until the second half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century that it was restored and remodelled.

The ground floor of the old monastery includes the Council Hall and the primitive pre-Romanesque church, which conserves the remains of mural decoration with scenes from the life of Saints Cosmas and Damian. On the upper floor, there is a courtyard, next to the Pantheon of Nobles, surrounded by smaller rooms. At the back is the church with a single nave and three apses. The cloister is located on the other side, surrounded by several chapels. The Royal Pantheon, from the Neoclassical period, is also preserved. A little further up is the new monastery, a grandiose building, now restored and refurbished. Part of it is used as a hotel.

- ALDEA, Joaquín (1748). Rasgo breve de el heroyco sucesso... San Juan de la Peña. Saragossa: Moreno

- BRIZ, Juan (1620). Historia de la fundación, y antiguedades de San Juan de la Peña. Saragossa: I. Lanaja

- BUESA, Domongo J. (1987). Obras en el monasterio alto de San Juan de la Peña (1815-1835). In Homenaje a Federico Balaguer. Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses

- DEL ARCO, Ricardo (1951). Noticias sobre el monasterio moderno de San Juan de la Peña. Argensola, núm. 6

- FERNÁNDEZ, Gloria (2002). Las pinturas de la Iglesia "baja" de San Juan de la Peña: Vínculos pictóricos entre el Poitou y Aragón durante el siglo XII. Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte, 14

- GALTIER, Fernando; i altres (2007). Monasterio de San Juan de la Peña. Gobierno de Aragón

- HERNANDO, Pedro (2019). Los prioratos de San Juan de la Peña anexionados durante el siglo XI. Universidad de Zaragoza

- LALIENA, Carlos (2006). La memoria real de San Juan de la Peña: Poder, carisma y legitimidad en Aragón en el siglo XI. Aragón en la Edad Media, núm. 19

- LAPEÑA, Ana Isabel (1989). El monasterio de San Juan de la Peña en la edad media. Saragossa: C. A. Inmaculada

- OLIVÁN, Francisco (1969). Los monasterios de San Juan de la Peña y Santa Cruz de la Serós. Saragossa

- PIFERRER, Pablo (1844). Recuerdos y bellezas de España. Aragón. Barcelona: J. Verdaguer

- UBIETO, Agustín (1999). Los monasterios medievales en Aragón. Saragossa: C. A. Inmaculada

- UBIETO, Antonio (1962). Cartulario de San Juan de la Peña. Vol. 1. València: Textos Medievales, 6

- UBIETO, Antonio (1963). Cartulario de San Juan de la Peña. Vol. 2. València: Textos Medievales, 9