The Abbey of Saint-Martin d’Ainay has traditionally been regarded as having very ancient origins. Gregory of Tours mentions the site of Athanaco, and tradition also holds that Saint Romanus († 463) was trained in this monastery during the first half of the fifth century, before withdrawing to Condat (Jura). Nevertheless, the earliest direct documentary evidence dates from the ninth century: in 859 its abbot, Aurelius, is mentioned, and he is credited with restoring the monastery, which was then abandoned.

Around 863, this abbot brought monks from the monastery of Bonneval (Eure-et-Loir) to reorganise the community, although they later returned to their original house. Aurelius was appointed Archbishop of Lyon in 875, but retained the office of abbot until his death in 895. In the tenth century the monastery was destroyed during a Hungarian raid and was restored once again by Abbot Amblard († 978). The present church was built at the end of the eleventh century and the beginning of the twelfth, and was consecrated by Pope Paschal II in 1107. From then on, the abbey enjoyed a long period of prosperity, gaining considerable prestige and accumulating extensive possessions, which were gradually lost as a result of a prolonged crisis that affected both observance and the institution itself.

In the fourteenth century a sumptuous abbatial palace was built, and in the fifteenth century significant works of renovation were carried out on the church. However, the relaxation of discipline, the introduction of the commendatory regime at 1507, and the destruction caused by the Wars of Religion (1562) led the monastery into decline. In 1685 it was secularised and placed under the care of a chapter of canons; in 1780 it even lost this status when it became a parish church. The Revolution resulted in the loss of its landed property, although the church itself was preserved by being used as a military storehouse, before later recovering its parish function.

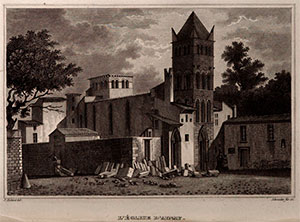

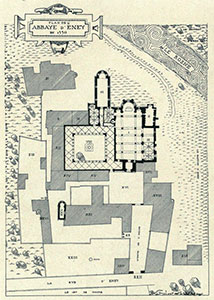

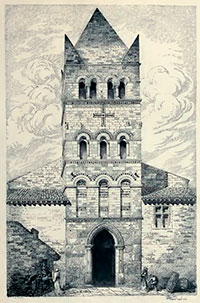

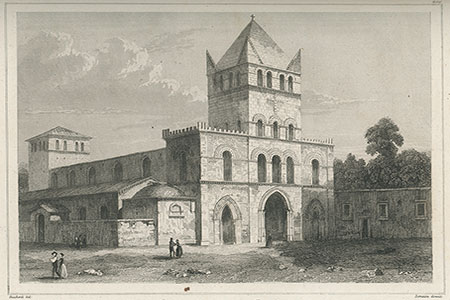

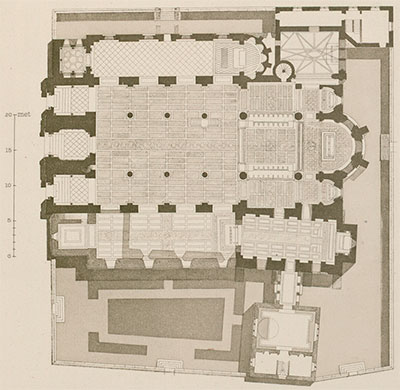

From 1835 onwards, an unfortunate restoration of the church was undertaken, transforming it into an essentially Neo-Romanesque building, although some medieval spaces and sculptural elements have survived. During this process, the remains of the cloister, already in a ruinous state, were destroyed. What remains of the medieval structure is the central core, with three four-bay aisles, an atrium with a bell tower on the western façade, a transept, and three semicircular apses aligned with the aisles, of which only the central one is externally visible. Modern alterations largely obscure the overall appearance.

- BAUDRILLART, Alfred (1909). Dictionnaire d'histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques. Vol. 1. París: Letouzey et Ané

- BERNARD, Aug. (1853). Cartulaire de l'Abbaye de Savigny. Suivi du Petit cartulaire de l'Abbaye d'Ainay. París: Imp. Impériale

- CHAGNY, André (1935). La basilique Saint-Martin d’Ainay et ses annexes. Lyon: Masson

- CHARPIN-FEUGEROLLES, Comte de (1885). Grand cartulaire de l'abbaye d'Ainay suivi d'un autre cartulaire redige en 1286 et de documents inedits. Lyon: Pitrat

- CLERJON, P. (1829). Histoire de Lyon, depuis sa fondation jusqu'à nos jours. Vol. 2. Lió: Laurent

- COTTINEAU, Laurent-Henri (1936). Répertoire topo-bibliographique des abbayes et prieurés. Vol. 1. Mâcon: Protat

- GUILLEMAIN, Jean (2004). Un monument de la réforme grégorienne, la mosaïque du sanctuaire d’Ainay. Bulletin de la Société historique, archéologique et littéraire de Lyon, vol. 32

- LE BAS, Philippe (1841). Historia de la Francia. Vol. 4. Barcelona: Imp. Nacional

- MARTIN, Jean-Baptiste i altres (1909). Histoire des églises et chapelles de Lyon. Vol. 2. Lió: Lardanchet

- OURSEL, Raymond (1990). Lyonnais, Dombes, Bugey et Savoie romans. La nuit des temps, 73. Zodiaque

- SAINT-ANDÉOL, Fernand de (1863). Notice sur l’église de Saint-Martin-d’Ainay. Les sept monuments chrétiens de Lyon antérieurs au XIe siècle. Lyon: France Littéraire

- SAINT-MAUR, Congregació de (1725). Gallia Christiana in provincias ecclesiasticas distributa. Vol. 4. París: Typographia Regia

- VACHET, Abbé (1895). Les anciens couvents de Lyon. Lió: Vitte